It is all very well to surmise what we supermen will be like; but an equally important question, so far largely skirted, is what it will feel like.

Miserable, maybe. In one of Robert Heinlein’s early stories, “By His Bootstraps,” the protagonist briefly encounters superhuman creatures via a timetravel machine, and his mind nearly crumbles:

It had not been fear of physical menace that had shaken his reason, nor the appearance of the creature-he could recall nothing of how it looked. It had been a feeling of sadness infinitely compounded ... a sense of tragedy, of grief insupportable and inescapable, of infinite weariness. He had been flicked with emotions many times too strong for his spiritual fiber and which he was no more fitted to experience than an oyster is to play the violin. (75)

There is ample precedent for this kind of conjecture. “Ignorance is bliss.” “Whosoever increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.” Perhaps our powers of perception, comprehension and sympathy will outstrip our ability to manipulate the world and ourselves, leaving us in the horrifying position of feeling and foreseeing every hurt, while helplessly watching universal tragedy unfold. it is even possible that this explains the apparent absence of superior alien visitors: cosmic truth, revealing itself at a slightly superhuman level, may be too terrible to be borne.

Optimists have not been lacking either, but their views have often been simplistic. Countless gospel-bearers have insisted that some ritual, or talisman, or slogan would make us moral and emotional-if not intellectual-supermen, with what small results we well know. And this penchant survives in the modern era: Arthur Koestler speaks of a “harmonizing pill” that will somehow reconcile our warring impulses and civilize us through chemistry. (91)

Since it is very unlikely to be that easy, many pundits refuse to consider basic change at all. Rene’ Dubos has written. “. . . I believe that any attempt to alter the fundamental being of man is a biological absurdity as well as an ethical monstrosity.” Also, “. . . the biological and mental nature of man ... is essentially unchangeable. “ (19)

But the “absurdity” remains to be seen, and the “monstrosity” is something we should be able to accept, albeit it will require some very nimble psychology. Expressed a little differently, it should be within our power to choose to grow up.

To a child, the normal adult has some monstrous qualities, including his inscrutable values and motivations. The boy is incapable, for example, of believing that one day girls will be alluring to him, or that lollipops may not be; and he cannot always understand the perspective that produces the apparent cruelties of punishment and discipline. Many children would opt for Peter Pan, and most adults to day would choose humanity. To undermine this prejudice, we must try to show that the suggested changes will indeed constitute growth, development, and improvement. The most crucial changes-the most threatening and promising ones-are those relating to intellect and personality. By investigating these, perhaps we can gain some inkling, some faint intimation, of what it will feel like to be a superman among supermen.

We can begin with something relatively simple, explicit, and palatable: the improvements in intellect associated with supertongue.

The Language of Superman

But what we can’t say we can’t say, and we can’t whistle it either. F. P. Ramsey

Since man is sometimes characterized as “the animal that talks”, perhaps superman is “the animal that talks more”, or the animal that talks better”.

Many scholars have been profoundly impressed by the idea that language does not merely express thought, but shapes it. Emerson said, “Bad rhetoric means bad men.” Ludwig Wittgenstein said, “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.” In Orwell’s world of 1984, “Newspeak” made it nearly impossible to express or even entertain thoughts outside the party line. Korzybski, Hayakawa and other students of semantics have laid great stress on the traps and pitfalls in everyday speech and symbolism .7’ And the great exponent of the hypothesis of linguistic relativity, or linguistic Weltanschauung, Benjamin Lee Whorf, wrote: “The world has to be organized by our minds-and this means largely by the linguistic systems in our minds ... we cannot talk at all except by subscribing to the organization and classification of data which the agreement (of the linguistic community) decrees.””’

This means, for example, that if your language is rich in special names for colors, you will have enhanced ability to recognize and identify particular hues from memory; and laboratory evidence has been compiled for this.” It has also been shown that if objects or stimuli are given the same name by the experimenter, the subjects are more likely to respond to them in the same way. (23) Yet many attempts to prove more sweeping claims have failed, and most linguists seem to remain skeptical of such assertions as, “...the structure of a particular language may channel thinking and thus cause the users of that language ... to arrive at different conclusions or different solutions to problems from what speakers of the other language would do. (23)

But this skepticism seems to be based on attempts to compare natural languages, with all the attendant difficulties in trying to sort out the linguistic effects from those of culture, heredity, etc. We do have good evidence, objective and subjective, that the languages of mathematics and technology permit and promote different and more effective styles of thinking. In the words of Sylvain Bromberger:

“. . some of these (scientific) questions may not be expressible in English at all, especially so if by ‘English’ we mean contemporary, ‘ordinary’ English. ‘Why is the emf induced in a coiled conductor a function of the rate of change of magnetic flux through it and of the resistance of the coil could probably not have been asked in seventeenth century English, and a similar situation may hold for questions that have not yet risen.” (16)

An even better example occurred in one of my classes a couple of years ago. Male students would go to almost any lengths to avoid the draft. Why? So as not to be killed in Viet Nam. But what was the probability of being killed there? Oh, fifty-fifty, was the usual answer. How do you know? Shrug. Don’t you know that about 40,000 have been killed, out of about 4,000,000 who have served? Shrug. The probability of an event is defined as its relative frequency of occurrence, in a suitable sequence of experiments it is the number of times it does occur, divided by the number of times it might occur. Calculate the probability of being killed in Viet Nam, if the war goes on about the same. Well, what do you know the probability of being killed is only 0.01 or 1%.

Hell no, they still won’t go, but at least their eyes have been opened a little bit, and if faced with really grim alternatives-jail or exile-the choice might now be different. One little technical word, and the concept it embraces, can change a whole life.

Again, the languages of science tend to reflect the “operational definition,” which separates information from mere labels. It was not so long ago, remember, that Moliere had to chide physicians for saying, in all seriousness, “Why does opium put people to sleep? Because it has dormitive virtue.” (“Because it puts people to sleep.”) We have much less tendency nowadays to talk about “virtues” and “essences” and “humors,” and this represents real progress.

Likewise, who can deny that quantitative thinking became much easier with the transition from Roman to Arabic numerals? (Imagine a Roman engineer trying to multiply LXIV by MCIX.) And who can doubt that the incredibly clumsy Mandarin writing exhausted the talents of generations of Chinese scholars? As Parkinson says, “. . . the process of becoming literate in China is one for which life hardly seems long enough.” (116) Although the Chinese invented movable type, the 40,000 characters of the written language prevented its use.

True, one might speculate that the very difficulties mentioned above tended to produce bright people; the Romans were, after all, effective engineers, and the Chinese did devise ways to put their language to work. But it is much more natural to recognize liabilities for what they are, and to agree, for example, with Professor Nakamura’s statement:

The (Japanese) language lacks the relative pronoun, “which”, standing for the antecedent, that helps develop clarity of thought. The absence of such a relational word makes it inconvenient to advance closely knit thinking in Japanese. It is difficult to tell what modifies what, when several adjectives or adverbs are juxtaposed. Because of these defects, Japanese presents difficulties for exact scientific expression and naturally handicaps the development of logical, scientific thinking among the Japanese people, which has actually brought about grave inconveniences in their practical Iives. (121)

Although Dr. Nakamura speaks here only of “difficulty” and “inconvenience;” much more than that is at stake. It is indeed difficult to compare the effects on culture of the natural languages (a) because it is nearly impossible to separate the nonlinguistic factors; (b) because a natural language, such as Chinese, that is deficient in one area may be superior in another; and (c) because all existing natural languages, including those of “primitive” peoples, are very old and complex. But by comparing natural languages on the one hand with protolanguages of the distant past, and on the other hand with the languages of science and with imagined languages of the future, we can convince ourselves that language holds a key to qualitative improvement in thought.

For example, modern Chinese is said to be rich in words for the concrete and particular, but very poor in words for the abstract and general; it also lacks simple forms for the plural of nouns or the tense or mood of verbs. (21) Thus they have no word meaning “old”one must specify how old, e.g., “seventy or more,” “eighty or ninety,” etc. Likewise, one cannot speak of a “fast horse,” but must say something like “a horse good for a thousand li.” The same word may signify “a man ... .. the man ... .. some men,” “mankind,” etc.

Of course the Chinese have long since found ways to minimize the deficiencies of their language, while exploiting its advantages. But what about protoChinese? There must have been a time in prehistory when Sinanthropus (or some such) was just learning to speak, and there existed words neither for “old” nor for particular numbers, neither for “fast” nor for units of distance, neither plural forms of nouns nor substitute expressions. Surely then, speech and thought must have been dim, vague, and ambiguous enough to merit the epithet “subhuman”.

Looking to the future, some opportunities are obvious but striking, as in the reduction of ambiguity. Questions in English, beginning with “Why,” are of so many subtly different types, demanding so many different kinds of answers often not the kind anticipated-that professional philosophers and linguists must write yards of jargon to extricate and explicate the meaning. (16) Supertongue should have all of these nicely categorized, with immense saving not only, of time but of misunderstanding and frustration.

Terseness is itself a virtue insufficiently appreciated. Who has not had the experience of reading a long sentence, involving difficult concepts, or complex relations, and found that at the end of the sentence he had forgotten the beginning? If you cannot express an idea briefly, then a combination of ideas may become so awkward that its expression is not just difficult, but impossible. Yet in English, for example, we use unnecessarily long words because most of the one-syllable words have not been allocated.

Consider, say, the one-syllable words that could be formed by combining three sounds-the first vowel, the first unvoiced consonant, and the first voiced consonant, viz., a (ah), b, f. Even if we delete the most awkward combinations (fba, bfa), there are still four words (abf, afb, baf, fab) only one of which (fab = “fob”) is in use. If we consider the sounds a, b, f and r, the feasible words are arbf, arfbl barf, braf, frab, and farb, not one of which is in use, except for the colloquial use of “barf”. In fact, linguists believe that with moderate ease we can speak and hear at least 100 simple sounds (40) whence it follows, with reasonable assumptions, that the entire unabridged English vocabulary could be reduced to words of one syllable-still leaving plenty of room for redundancy, synonyms, poetic variation, and the monosyllabic rendition of a large store of common phrases!

Our languages are exceedingly weak also in the description of contoured surfaces, including faces; we can easily recognize differences of physiognomy and expression that we are nearly helpless to communicate verbally. Consider how laborious it is for a witness to help a police artist reconstruct a face; or, better yet, consider the well-documented story of Clever Hans. (119)

Hans was a horse-a horse that apparently could do arithmetic, understanding the questions spoken in German (this was in Berlin in 1904), and responding with the correct number by tapping his hoof. Visitors, including eminent scholars, came from far and wide to view the marvel; and many were convinced of the genuineness of Hans’ intelligence, because he succeeded with strangers as well as with his master, even in his master’s absence.

Eventually, however, a shrewd observer named Pfungst noticed that Hans did poorly in failing light, and with that clue the puzzle was quickly solved. Hans had no talent whatever in arithmetic and no understanding of German; what he did possess, however, was an amazing ability to read human emotions from facial expressions and bodily attitudes. He simply (!) watched the spectators carefully, and could tell by their appearance when it was time to stop tapping. We can expect languages of the future to have thousands of new words and coded combinations, both to allow the communication of subtleties of facial expression and to help perceive them.

Again, we need to develop the verbalization of kinaesthesia-articulate the sensations relating to balance and coordinated movements. At present, in order to teach someone how to ride a bicycle, for example, it is necessary to demonstrate and then let him practice. Conceivably, with adequately developed language, one could simply give description and directions, and the feelings and muscle responses would be so clearly conveyed that the student could ride at once, or at least with greatly reduced practice. (Fortunately, new techniques of memory training are likely to be at hand even before we have biologically improved brains.)

Oddly enough, some bright people have failed to recognize the opportunities in more sophisticated language. The philosopher Michael Polanyi, for example, actually appears to accept the present limitations of language as natural and permanent, and uses them to “prove” (!) that some kinds of knowledge cannot be made explicit, that certain things can be known only tacitly: bicycleriding is one of his examples. 141 Now, it is not selfevident that the feel of a bike can be fully conveyed in words, but at least the approximation is presumptive. If one can remember or imagine a set of feelings, then one can associate these with a spoken cue. The problem then reduces to building an adequate store of feelings or responses on the one hand, and symbols on the other.

Thus, superman will gradually build-and be built by the richness and subtlety of supertongue, and there will develop qualitative changes in our mental world, if these suggestions prove sound. We should be able to express details, shadings, and nuances that now perforce we must either gloss over, or else honor at the cost of excessive labor and time. Our perceptions of the world, and of each other, should in turn become sharper, broader, and deeper. Thoughts which formerly could be expressed, or even entertained, only slowly and laboriously if at all, could then become for everyone the casual exercise of a moment. What godlike power, just in the enrichment of verbal language!

Eventually, the demands of “channel width” for high density communication, or the simple joy of exploitation, may lead us to explore visual, tactile, and olfactory dimensions of language, despite the seeming handicaps. We may learn how to create appropriate signals with muscles or glands, or even directly by cerebration, as well as how to amplify these signals and beam them over space, and how to use suitable transducers for direct input to the nervous system of the listener. But such exotic techniques will not soon be needed. Sound alone provides vast room for the expansion of language.

The consequences are in some respects unnerving. It gives one pause, for example, to note-as I have elsewhere--that within a few centuries Shakespeare is likely to be a dead letter, his wonderful works of no more interest than the grunting of swine in a wallow. At best, they may retain a certain quaint charm for scholars of antiquity, somewhat as Egyptian hieroglyphics do for us; but ancient Egyptian writing is simply too stiff, narrow, cumbersome and tedious to merit much interest among modems, even though it was created by people just as intelligent as we. It was a feat in its time and served a purpose, but now it is over and done with. If we would not remain children, then at the appropriate time we must put aside childish things.

The Human Condition and Beyond

An adult differs from a child in more than size and strength, and we can expect our thoughts to develop in more ways than speed and accuracy, as well as anticipate a different balance in our feelings and an altered focus in our motivations. Our guesses will be informed by a review of certain aspects of human psychology.

First we must clear away certain fallacies widely held among “educated” laymen, (for example, many physicians), such as the notion that the most powerful of our drives are those related to survival, food, and sex. For people to risk their lives, and to abstain from food and sex in varying degree in response to social pressure, individual idiosyncrasy, or mere habit, is more the rule than the exception. (Think of soldiers, smokers, dieters, chaste teenagers, etc.). While our elementary animal needs are in a sense “basic”, still the tail has come to wag the dog, and the higher drives are nearly autonomous. Gordon Allport has not much overstated the case in saying, “The motives of a mature person are so far removed from the original physiological drives that nothing can be gained by attributing the social behavior of an adult to primary physiological drives.”’

Another mistake is the notion that we are governed, or ought to be, by some principle of “homeostasis” analogous to the tendency of an individual cell to maintain a constant internal environment in the face of changing external conditions. Only some aspects of our behavior, and those not the highest, are of this defensive type, aimed at redressing a balance and seeking some peaceful haven. (This is the trouble with virtually all utopias.) A somewhat similar error is the idea that one of our basic motivations is to seek “adjustment” to the world. Probably most of our highest drives are related to the nonhomeostatic, aggressive drives of curiosity, play, manipulation, and exploration. At any rate, happiness cannot be equated in any simplistic way with comfort or pleasure, else the opium eater and lobotomy patient would have to be considered among the most successful people.

Then there are several interrelated fallacies, seldom explicitly stated but prevalent, concerning “natural” man, already touched upon. One is the assumption that our most basic motivations and values are mutually consistent, so that a “correct” attitude and course of action is always possible in principle: this is far from clear, and to avoid permanent residence on the horns of a multiple dilemma it may become necessary to excise certain motivations from our psyches-a painful process. Another is the idea that man is normally well integrated, despite the many-layered accretion of disparate elements in his brain and mind gathered during the development of the species and the individual.

Still another is the assumption that the more basic drives, at least, are overwhelmingly adaptive, for example, that fear is almost entirely a useful response that prepares the organism for “flight or fight”; but M. B. Arnold has shown rather convincingly that fear is more often enervating than invigorating, and while it may be useful for caution it is maladaptive for flight.’ Finally-to cut the list arbitrarily short-there is the idea among many laymen that needs and appetites are always well correlated; but P. T. Young points out that this is not so, e.g. that when a rat’s diet is deficient in magnesium, it may actually develop an aversion to the needed element. 185 In short, it seems nearly certain that man is not consonant either with himself or with even an idealized environment.

Those who speak of the “human condition”--especially novelists and philosophers--often embrace all of these fallacies and many others. In their moments of relative optimism they may rationalize pain and failure as necessary counter-points to joy and triumph; or they may see tragedy as the penalty for forsaking the “natural man” within us, the generic angel sullied and crusted over by individual and cultural mistakes. These are not very productive ideas--little more than breast-beating. In their more pessimistic musings, such writers are likely to see the failure of man as an existential necessity, hungers unsatisfied and tensions unalleviated as the way of the world-but again they only bewail man’s fate or acclaim his noble martyrdom, and neglect the close analysis of the problems that might reveal paths to solutions.

As one small example, it is suggestive to imagine the plight of a young man in the Old Stone Age, seeking to “find himself.” Why can he not adjust to his time and place, as might be expected of a “normal,” healthy animal? Why is be restive and discontented, even though his life may be comfortable enough in a good year, with clams for the digging, fruits for the picking, a complaisant woman and a balmy breeze? Perhaps he is really a jazz musician, and be can’t find a clarinet. Possibly be needs to do fine wood carving, and the flint band-axe isn’t adequate. Or maybe--just like some moderns-he needs to scratch his fanaticism itch; he needs a “cause,” and no satisfactory banner is in sight.... Well, there was little he could do but kick the dog, squint wistfully at the horizon, and grumble about the “human condition.” But our position, at the watershed of history, is different; we have the knowledge, the tools-and the time. To plan our strategy, we need among other things the clearest possible understanding of motivation and emotion, some of which seems at hand.

Motivation: Hierarchies and Feedbacks

There are several related words which differ in many ways-between themselves, from psychologist to psychologist, with respect to inheritance vs. learning, etc.; these words include motivation, drive, and instinct. We shall not trouble ourselves overmuch with the distinctions, but use them (as Humpty-Dumpty did) at our convenience.

As good reductionists, we recognize that at the basic physiological level our nervous systems (hence our personalities) are programmed, and that a motivation (drive, instinct, reflex, habit, etc.) is an element of the programming. At some stage, presumably, the programming and its principles will be fully understood and it will be within our power to modify it physically, by brute force if necessary, thus becoming whatever we choose to be with in whatever limits may exist. At the very least, each of us should become equal to the best of us in all respects.

But this is rather vague and distant. For the near term, we must work at a different level and more indirectly; and of course we acknowledge that the programming of an animal is far different from that of a computer, primarily because, even in self-modifying computers, there is a clear separation between the “nervous system” (the program) and the balance of the beast. In a biological organism this distinction is not nearly so sharp and the feedbacks much more complex, including the likelihood of internal anomalies or inconsistencies, such as the simultaneous need to dominate and to submit.

In Abraham H. Maslow’s frequently-cited theory of motivation, various drives or goals are roughly ranked in order of “prepotency” or urgency, and the “lower” drives must be satisfied before one can turn to the “higher,” in general.”’ For example, hunger usually takes precedence over the sex drive; and most of us require our social approval urge to be satisfied before we can turn fully toward self-actualization or fulfillment of creative potential. (Sometimes, of course, the same activities may serve both ends.)

Maslow’s theory, although crude and incomplete, is not merely descriptive but useful and fruitful. It organizes motives into hierarchies (which admittedly are not always clear-cut), and it also distinguishes between “deficiency motivation” (such as hunger) and “growth motivation,” of which the highest is self-actualization: a man must do what he can do. (As Henry W. Nissen put it, “Capacity is its own motivation.”) Among other things, these ideas, when judiciously interpreted, give us a new perspective on the autonomy of the higher motivations and the possible dispensability of some of the lower ones.

As a trivial example of the partial dispensability of one of the lower drives, consider hunger. Modern man-let alone superman does not need gnawing, ravenous hunger to produce needed action; if we happen to be busy, we should be able to ignore hunger for several days without severe discomfort. There is no danger of starvation; we know our bodies need food, and it will be available at our convenience. Instead of a raucous “alarm clock” clanging feed me, feed me, there should be a decorous, gentle “chime” growing more insistent only very gradually.

Ideally, of course, the “alarm” should also be adjustable by an act of will, so that when we decide to enjoy the act of satiating a vigorous appetite, the appetite will be there. To attain these improvements should be a relatively easy task of physiological engineering, if indeed not merely of conditioning.

At the second-highest level in Maslow’s system is the need for esteem, that of others and of oneself. A great many people are more or less stuck at this level, their major activities organized by this need, which never seems quite satisfied. There seem to be two main reasons for this: first, the need was insufficiently satisfied early in life, and the deprivation, according to Maslow, permanently weakened the individual in that respect-made him less able to bear that kind of deprivation than a normal person; second, the deprivation instigated activities that became fixed as habit patterns, so that esteem-bringing activities (making money, earning acclaim and admiration, etc.) became essentially autonomous, the core of the individual’s personality, dominating all other needs and activities, at the expense of his further development.

It is fairly clear that, as supermen, we can largely dispense with the esteem drive also. (We bypass for the moment the question of how to reorganize personalities already stuck at that level.) By way of analogy, normal people in civilized countries and quiet times (there have been such) are very little driven by their “safety needs” (the second tier in Maslow’s hierarchy) because family and society have always provided ample protection, and the adult need merely allocate an occasional cursory review to his arrangements for physical safety. Likewise, superman should have ample confidence in the esteem-worthy character of his personality and actions, and thus be abie largely to ignore the question, except for occasional routine review on a conscious level.

If superman is going to eliminate or minimize all motivations except self-actualization, this seems to tell us something about the nature of “happiness”; it does not depend primarily on comfort, certainly not on safety, and not even on love or self-esteem, although all of these are needed in their time and place; it depends ultimately on a certain tension, and a certain rhythm, in the stretching and exercising of one’s capacities-not homeostasis, not any static bliss, but a dynamic and intricate pulse and surge of challenge and growth. Happiness is better than comfort, joy, or even ecstasy; and its main features seem to relate to the binding of time and of the personality--it seems to tend, in a preconscious way, to depend on rhythms of satisfaction extended over time and over several facets of the self.

While these notions barely broach the subject, and while vast areas of great interest must be omitted entirely (such as the nature of the unconscious and the possibility of making it rational and accessible), still we may get a glimmer of the transhuman psyche by looking at some further aspects of motivation, usually either from a Maslowian or a Darwinian point of view, and with no special concern for redundance. But before looking at some specific motivations, we should clarify again the possibility and desirability of a higher level of uniformity, and a much larger pleasure/pain ratio, in our transhuman world.

Designing Personality and Prescribing Happiness

When we learn what factors of personality are most conducive to external effectiveness and to internal satisfactions, everyone should have the option of optimizing the circuits in his nervous system, whether through surgery, pharmacy, and electronics or through simple learning. Then almost everyone might be highly efficient and nearly always content, maybe even euphoric; yet contemporaries are apt to view such prospects as distasteful or worse. We must try to show that the fear and repugnance many feel are founded mostly on misunderstanding.

Part of the fear pertains to a well-meaning but clumsy and doctrinaire paternalism in the manner of Brave New World, which some humanists foresee, a world in which you will not only be forced to conform, but will jolly well be forced to like it. The fear of being made to like what you don’t like strikes at the ego, the self; a threat of forced personality change is, in a sense, a death threat.

The possibilities of abuse and tragedy are real enough. But such errors represent aberrations and not necessary consequences of human engineering. As for the feeling that any major personality change is a mortal danger, that is just an excess of wariness and want of thought; the feelings that make our hackles rise are not always reliable guides to behavior. Major progress must involve major changes in intellect and personality, and there need be no trauma unless the change is too rapid or disorderly. If we have time to digest and integrate the new information and relationships so that all aspects of the self can be kept or brought in phase, then these personality changes will represent not mayhem but simply growth, and in many cases healing.

Even less valid is the notion that some of the spice will be taken from life if we cold-bloodedly study the psyche, learn its mechanisms, and then tailor the individual to exploit this knowledge. It takes all kinds to make a “human” world, we are told; some even go so far as to say it is our very defects that are endearing!

Perhaps it is the contrasts in the world which provide some of its interest. But who would conclude thereby that we ought carefully preserve a quota of victims, a class of clowns? Must there be dwarfs, and blind men, and hunch-backs, just so the rest of us can savor our good fortune a little more? Must we force or entice some to remain simpletons, so the rest of us can the better relish our superiority? The absurdity of such proposals is obvious; it would be even worse than to retain a class of poor people, just to titillate the rich.

Even if it were true that the world would lose some savor thereby, it would still be morally and practically necessary to allow everyone the information and facilities to optimize himself, to enjoy the best available. But in fact it is not true, for at least two reasons. First, it would require a warped mind to enjoy the unnecessary misfortune of others. Second, superman’s capacity for perception is unlikely to require the crude, physical, temporal presence of contrasts of misery; if be realizes fully that misfortune has existed, and could exist, that should suffice for any requirements of contrast.

In similar vein, some philosophers have gone so far as to assert that pain is necessary for pleasure, occasional misery is essential for the possibility of joy, good cannot exist without evil, and indeed life can have no meaning without death. This falls just short of being self-evident drivel; it has just barely enough plausibility so that it sometimes fools people.

The answer, first, is that it just isn’t true; it is an assertion with a certain ring to it, but virtually no substance. There is no solid evidence behind it, and there are plenty of counter-examples. There are many people who are generally wretched, and others who are generally contented. Many people show a life-long surplus of joy, and others a deficit.

If the claim is made that at least a substantial danger of pain must be present, that at least a looming threat of tragedy must underlie the enjoyment of life, again the case is, at most, unproved. To some extent, the argument can be reversed: the near presence of unfortunate people and the dark shadow of peril can warp the personality, producing feelings of guilt and anxiety that make happiness impossible.

In any case, as already indicated, superman should fully appreciate the dangers and tragedies in the world of space and time, and be able to utilize any desired sense of contrast. Furthermore, we do not expect this functioning to depend on the crude animal drives which governed our predecessors and ourselves until now; for superman, gradations of pleasure ought to provide motivation just as efficient as did the contrasts of pleasure and pain for man and preman. Keenly alive to the implications of small differences, he can be happy at all times and comfortable most of the time, yet far quicker and more energetic than we in responding to-and creating-demands for action. This qualitative improvement is something we can scarcely understand until we experience it.

Habits Good and Bad; Phasing Out Fear

With no effort to be systematic, let alone exhaustive, we can now look at a few specific drives and ask whether to cultivate or weed them out.

While we are being very cavalier in the use of terms, there seem to be very few, if any, true “instincts” in man above the cellular level only genetic tendencies or capacities which are stronger or weaker, more or less specific. (It used to be said that infants have two universal instinctive fears, namely of falling and of loud noises, but this seems to have been disproved,’) One is tempted to speak of a universal tendency to avoid the painful or unpleasant and seek pleasure, but the spectacle of a sadist and masochist interacting is enough to cure us of that; adequate definitions of pleasure” and “pain” are not yet at hand.

Having bowed to some of the many difficulties, we can now proceed to ignore most of them and make some judicious speculations. Our first and easiest include the continuation, without radical change, of the drives of self preservation, curiosity, and general aggressiveness. It is not claimed that these are “basic” in any physiological sense, and it is even possible that aggressiveness and selfpreservation may have neurotic elements from some valid point of view; but it is reasonably clear that these traits will persist simply because their lack would probably prove fatal in the end. It is true that clams have done well enough, as a species, without notable curiosity or aggressiveness, and even some varieties of man-Egypt’s fellahin, for example-have sometimes found protected niches; but on the level of technological man, and for the long term, a lack of curiosity and aggressiveness will surely be suicidal. (Their presence may also, of course, but less definitely.) To him who merely sits and waits, assuredly will come at last his nemesis; constant reconnoitering and probing is the only defense that has a chance. The only way to avoid disaster is to go looking for it.

Drives likely to be extirpated include zealotry (idealism, fanaticism, militant enthusiasm, etc.) and the “territorial imperative,” if the latter really has a specific genetic basis. These are not only unnecessary, at a superhuman intellectual level, but obviously troublesome; we shall expand on this in the next chapter. Shame will probably be weeded out, no longer being needed as a counterweight to pride; instead, there could be simple acknowledgements of factual shortcomings, and calm regret when we blunder, followed by efficient corrective actions. On the other band, we may well retain pride and vanity, despite their elements of neurosis, because they may continue to be important constituents of our psychic fuel.

More impressive than any of these, however, will be the expected phasing out of fear.

Fear has both emotional and motivational aspects. It seizes the viscera and alters the metabolism, often squeezingthe heart and blanching the face; and it provides powerful motivation in a wide variety of useful avoidance habits. It is usually assumed to be a biological basic, and of all Franklin Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms, freedom from fear might seem the least likely of attainment. Short of utopias, short of total control of the environment and a stable society-must there not always be dangers? And is not fear a necessary response to danger? Would not a fearless being tend to die rather quickly? Is not fear tightly bound up with the survival instinct? So it might seem: nevertheless I think that, as supermen, we shall be nearly fearless.

For this discussion we must disregard most of the complexities and subtleties, such as the relation of fear to the feelings of anger and awe. Then the evolutionary bases of fear and courage seem fairly clear, and these form a dynamic tension somewhat analogous to that of self preservation vs. self sacrifice, discussed in Chapter 7. This tension, also, could become radically displaced.

The utility of fear is obvious in avoiding physical peril (a predator, an enemy, a storm). Fear leads to flight or avoidance, and flight or avoidance may lead to safety; hence the timid tend to survive. But the meek have not inherited the earth, because flight or avoidance does not solve all problems: if predators lurk around the only water hole, then those who cannot overcome their fear will die of thirst. Warriors in a warlike tribe may lead risky lives, but they tend to acquire women, land, and slaves, thus consolidating their ferocious traits. (It is said that, a few centuries back, the life expectancy of the sons of English earls was about twenty three, most of them dying violent deaths.) There is probably no single gene for fear, no simple hereditary basis for courage or aggressiveness, but we all have both tendencies in varying degree.

Some of the disadvantages of a fearful disposition are manifest. To begin with, it is unpleasant. If excessive, it can be drastically counterproductive: useful caution may deteriorate into harmful terror or panic. On a more subtle level, in modern circumstances, fear may be diluted or Ic referred”, expressing itself as guilt, anxiety, and indecision. Do these represent the inescapable price we must pay for a biologically essential response? I think not.

At the very least, the average level of fear can be sharply reduced. A child needs fear, because he is too immature to be governed by reason based on experience and understanding; only a healthy respect for parental anger will keep him out of the street. The adult, on the other hand, does not have to be terrified of automobiles to avoid them: he dodges the taxicabs efficiently but calmly, using his brains and rarely calling on his adrenal glands for assistance.

When we are sufficiently alert and aware, we should not need the spur of fear, nor tolerate the confusion it tends to bring. Our glandular responses can probably be brought almost entirely under conscious control, by techniques we are already beginning to learn . (81) Again, this may convey images of aloof, imperturbable automatons, cold and bard, but this is not the right picture. After all, when we grow up today and leave behind our temper tantrums, this does not make us less human, only less childish.

It is commonplace--especially in war--to say that everyone has fear, that courage is not the absence of fear but the ability to overcome it. The first part of this saying is an egalitarian myth, as I am convinced by observations of different people and of myself at different times. There are wide variations in habitual fear levels and fearful response habits, and there is indeed a type of bravery based on lack of fear; there really is a temperament which is cool and steady in the face of danger. Two fighter pilots, for example, may be perfectly equal in willingness to accept and seek risks, but the one with less fear to subdue is likely to be more clearheaded and efficient.

This cool temperament is partly inherited, but it can also be acquired. In my middle age, I am much less fearful than I was as a child or youth. Some of this fear reduction may result, to be sure, from diminished sensitivity-our antennae become stiffer with age-but introspection convinces me that some of it represents genuine learning and growth, the ability to size up dangers, put them in perspective, and handle them in a relatively calm way.

Phasing out fear is only one small aspect of the improvement expected in our personalities as supermen, but it is one most of us can understand and appreciate readily. Not to shiver, not to quake, not to feel the knot in one’s stomach, not to be gripped by the shrinking confusion of mind or paralysis of will not to be afraid any more, how marvelous!

The Action Approach

If wishes were horses, beggars would ride. It is all very well, some may say, to speak glibly of extirpating this instinct or phasing out that emotion or drive, but exactly how can this be done?

In part, the question is unfair; if we knew exactly how to do it, it would already be done, and we would be superhuman now. In part, we rely on our sense of history and on the validity of our world-view: presumptively, there is some specific anatomical and physiological basis for every constellation of traits, and the day must come when we can remake ourselves at least to the level of the best that now exists, using either grossly physical (surgical/ chemical/ electronic) or psychological methods. Beginnings and hints of all these capabilities exist in the current technical literature. In this section we want to review briefly some of the simpler techniques, characterized by Dr. George Weinberg, a New York psychotherapist, as “the action approach.” (116)

The basic idea is simple and has been around a long time, viz., that many aspects of personality can be regarded as habits, which can be inculcated or eradicated by patterns of behavior that are under conscious control. For a long time attempts to apply this idea had very limited success, but its modern champions are undaunted and apparently making considerable progress.

They are bucking a majority which still takes a gloomy view about the possibility of teaching old dogs new tricks. For example, P. M. Symonds has written, “The evidence ... points not only to the persistence of traits of personality throughout life but also to the great resistance of personality traits to change ... after months and even years of concentrated efforts (by clinical workers) to change personality in clients, basic personality patterns remain unchanged.” (161) Gardner Lindzey et al have found compelling evidence for the importance of genetic factors underlying certain personality traits.”’ And the psychoanalytic school, beginning with Freud, holds that events in early life exert influences exceedingly bard to counteract, a view which is certainly consistent with the indifferent success of analytic methods.

What Weinberg calls “the action approach” is related to what others call “behavior therapy,” an early proponent of which was William James, who said, “Action seems to follow feeling, but really action and feeling go together, and by regulating the action, which is under the more direct control of the will, we can indirectly regulate the feeling, which is not.” (Remember “Whistle a Happy Tune” in The King and I) If we act like the people we want to become, according to James, we shall turn ourselves into those people. But this cannot be done instantly, hence it is crucially important to choose the right strategy in modifying first one, then another of the behavior patterns in question. Weinberg’s contribution-which we cannot detail here--lies in the explication of this strategy, and be claims substantial clinical success.

Maslow’s views are at least partly consonant with these ideas. He speaks of an “inner core” of the personality, formed in the first few years of life, which must be discovered if one is to find his “identity”; but he also says of the self, “Partly it is also a creation of the person himself ... Every person is, in part, ‘his own project,’ and makes himself.”’ “ Again, the tail wags the dog, and at least an important part of the person is simply a bundle of autonomous habits, subject to change.

The better known behavioral therapists, e.g. H. J. Eysenck, have a somewhat different focus in applying learning theory to the elimination of neurotic symptoms, often using a simple “conditioning” approach remindful of Watson’s work with animals; for example, a child may be cured of bedwetting simply by wiring the bed so that a bell rings whenever he begins to urinate. (48)

Needless to say, the analysts vigorously attack the behaviorists, claiming among other criticisms that a symptom eliminated by conditioning is likely to be replaced by another symptom, perhaps worse, if the “underlying unconscious” cause is not removed; but the behaviorists insist the facts support them, and that in many cases, at least, there is no “unconscious cause,” but only the syndrome itself.

Weinberg’s position is in some important respects different from that of the classical behaviorists, particularly in his attention to the total patient and his motivations, rather than to isolated syndromes. But he is also attacked by the analysts, and has some wry comments about those who insist that a “seeming” personality change leaves one “really” the same underneath, however great the objective and subjective improvement may be.

We have not proven that “normal” people can be much improved by the same techniques that are used with neurotics,” but no one is fully normal anyhow, and nearly all of us could probably be substantially improved by the systematic use of existing techniques. If we include “operant conditioning,” by means of which one can apparently attain conscious control even of his heart beat and brain waves, then this partial and current armamentarium alone gives promise of a giant step forward.

Emotional Stability

Despite the foregoing notes of optimism, superman will need all the help be can get in stabilizing his emotions. We think we have troubles now! What must we expect when our expanded intellects interact with a vastly more complex environment?

One possibility is Heinlein’s conjecture at the beginning of this chapter-everything scaled larger, including gulfs of grief that humans would dare not plumb, as well as (presumably) peaks of ecstasy that unmodified man could not endure. But we can do without the gulfs, thank you, and there are many ways in which we might cheat the piper, such as simply to tune out or wall off the undesired emotions, possibly for protracted periods, until we can deal with them, perhaps piecemeal, from a more advantageous position. Of course this strategy usually fails for the neurotic and psychotic humans who try it, but that is because (a) their unconscious minds are not under control, and (b) they never achieve the more advantageous positions that continual growth should bring.

Another critical problem is that of monitoring one’s own conditioning. According to Eysenck dysthymic (despondent) patients and normal introverts are characterized by the quick and strong formation of conditioned responses, while psychopaths and normal extraverts are characterized by the weak and slow formation of conditioned responses. Thus the deviation in either direction may prove disastrous. (49) And this is oversimplified; our problem will be to screen endless categories of conditioning reactions and optimize the rate and degree of each. There are some things that we want to learn thoroughly, in a single lesson mathematical theorems and tables of basic information, how to walk without stumbling in the reduced gravity of the moon, how to recognize poison mushrooms, etc. Then there are other things that we want to learn only through thick (but not impassable) barriers of suspicion-that our value systems are wrong, that a friend is stabbing us in the back, or that it is necessary to betray a commitment, for example.

A related problem is that of adjustment versus responsibility. In contemporary life we all know easygoing people who have apparently made a marvelous adjustment-by blinding themselves to dangers and responsibilities (for example, letting children run wild, untrained and unprotected); and on the other band, there are those who assume more responsibility than they can handle, and succumb to neurotic anxiety. The latter will be the greater danger for superman, whose longer attention span and heightened awareness of implications may tend to overwhelm him with demands.

Finally, large elements of uncertainty will always be present when we have no fixed ultimate goal, when the horizon continually recedes as we advance, when being is subordinate to becoming for the indefinite future. As Maslow put it, “Growth has not only rewards and pleasures but also many intrinsic pains.... Each step forward is a step into the unfamiliar and is possibly dangerous. It also means giving up something familiar and good and satisfying. It frequently means a parting and a separation, with consequent nostalgia, loneliness and mourning. . . . Growth forward is in spite of these losses and therefore requires courage and strength in the individual....”

There is no guarantee that the requisite courage and strength will always be found in time, but I am reasonably confident we can gain sufficient control of our nervous systems, so that the major threats will not be from within.

Empathy Without Altruism

We often assume that superior beings will be characterized by the “civilized” satisfactions and the gentler virtues. Superman must be nice-a kind of Boy Scout idealized and realized. But this notion is probably as unrealistic as its opposite, that of the bloodless logicmachine.

Today we love to be loved, and we need to be needed; the most valued feeling is the feeling of being valued. (That is, most of us are stuck on Maslow’s third or fourth level.) But advanced individuals may see maudlin sentiment on the part of their fellows as worse than useless, as a pitfall for the object of affection and a sign of weakness and immaturity by the giver of affection. They may learn to enjoy each other’s company and shared activities no less, while still refraining from a generalized and uncritical attachment. Today it is regarded as a virtue to give oneself and to want to give oneself, but this may come to be seen only as a neurotic weakness.

As for the particular trait of generosity, we may be able to throw light on some of its aspects by considering the word itself. “Generosity” is usually construed as giving more than is needful, or more than is expected, or more than is customary. But to understand the anatomy of this generosity, we must ask what is needful, and why; what underlies the expectations and the customs.

What is our purpose in giving more than is needful, or expected, or customary? If it is to inspire gratitude, because we enjoy the gratitude or want to benefit from it, then giving that much was needful after all, and in a private sense the generosity did not exist. If our motives were more neurotic, if we needed to bolster our selfesteem or assuage guilt feelings, then again, in a subjective sense, no generosity was involved. In the last analysis, we do everything to please ourselves, or to please some aspect of ourselves, or to avoid a worse eventuality (even though our actions do not always lead to the desired results); thus we can say, with great generality, that in a proper subjective sense there is no such thing as generosity.

This is not to deny that the word has a useful meaning, or that some people are nicer than others. If someone you know has what is commonly called a generous nature, then be doubtless does give beyond the average, by objective criteria, and he doubtless is a more pleasant person to deal with (although sometimes his generosity may have bad results for his family, as well as for himself). But superman may regard the satisfactions of the generous as the delusions of fools, more or less in a class with those who packed off their little ones on the Children’s Crusade, feeling full of pious virtue; or with the Stakhanovites who work themselves into early graves for Mother Russia and the Party.

Perhaps, then, superman will regard generosity and niggardliness alike merely as miscalculations, carrying emotional freight only for the immature. (One gives what suits one’s purposes, neither more nor less.) Despite this, he may feel the same warm glow a human does when helping and benefiting others; among his other accomplishments, superman will surely not lack the capacity for doublethink, and for falling into childlike attitudes when he chooses.

So in some respects we may indeed come near the cold, aloof, machinelike creature so often depicted in fiction. Surely it will be an advantage to be able to “turn off” or “tune out” one’s emotions at will, choosing fully to savor only those that are enjoyable-provided this can be done without impairing judgement and without traumatizing the unconscious mind. Perhaps we may carry to extreme our present habit of “hypocritical” courtesy, showing our acquaintances faces of concern and interest that we may not fully feel, or allow ourselves to feel-not because we are deceitful, but because we recognize both their need for sympathy and our need to limit involvement.

But along with his coolness, his ability to make the grimmest decisions without the quiver of a muscle, the transhuman may also be warm and understanding in a way that we see only few hints of today. A “generation gap,” for instance, should be a thing unthinkable. Every parent should understand the most delicate nuance of his child’s feelings and the wellsprings of his motivation. In part, we think of the development and training of accentuated perceptions, a la Clever Hans, mentioned earlier. “Every little movement has a meaning all its own,” and an adult should be able to “read” every twitch and grimace of a child. He should also sense the child’s feelings more intensely, for two reasons: the higher “voltage” of his nervous system, in contrast to ours; and his superior ability to extrapolate consequences and perceive the relatedness of situations and developments. All this means he can convey to the child the breadth and depth of his understanding and sympathy, yet with enormous tact-the total result being a sense of love that we would find inexpressible. Supermother--whether she “carries” her child or watches him gestate in an artificial uterus--will doubtless look back on human mothers, insensitive and erratic as they are, as little better than the sow that requires only a small disturbance to cannibalize her young.

Man and Superman

Although the foregoing discussion of superman’s personality was only a tentative beginning, limitations of space and competence force me to leave it at that. With luck, these speculations may help make transhumanity just a little more meaningful, a trifle less vague and abstract. Possibly more psychologists will be motivated to think in terms of therapy for “normal” people as well as for neurotics; surely this is a major untapped national and personal resource, right now. Perhaps some poets and novelists will be moved to make these ideas more particular and dramatic in the next few years, helping to pave the way for superman and create a more active demand. But might there not be a dangerous interregnum as man is phased out and superman takes over?

The question of race and culture in politics is already volatile, and may become more so. Unless government controls are imposed--which hopefully will not happen--life styles and initiatives will continue multifarious, and for a while many varieties of superman will have to get along with each other, and with man.

One of the more obvious dangers is probably exaggerated: that of nations or societies cloning “superior” types, using newly developed biological techniques to produce thousandfold “twins” of Einstein, Patton, Eddie Rickenbacker, and others who supposedly might beef up a country’s strength. For one thing, these procedures are not likely to be available until the present generation of doctrinaire leaders in the totalitarian countries has been replaced. For another, it should become obvious in time that (1) a hundred Pattons are not a hundred times as valuable as one, and (2) it is nearly impossible to surmise, even a few years ahead, which traits are the most valuable ones for specific strategic objectives; one cannot even be sure whether big men or little men will be better soldiers in the context of the next decade’s technology. But most of all, we rest our hopes on the emergence of individual, selfish motives and the millennial outlook, which will view with cold disfavor any holy wars or ideological crusades.

There will still be problems, but to some extent they may create their own solutions. If a new variety is really a superman in all respects, he will realize, far better than we, the error in mistreating inferiors and the folly of boastfulness or arrogance. But there may be many limited supermen, especially in the near future, and they will not necessarily have balanced judgement; some of them may be only strong, and not very sympathetic or wise. Still, at least two factors should tend to save the situation: heterogeneity and upward mobility.

If a subpopulation is segregated geographically and culturally, as well as genetically, so that it is highly visible and enviable, then it has an explosive potential; but that is not likely to be the case. It will be more similar to the present situation of the wealthy: They are widely scattered, widely variable, and not, to any important degree, leagued together against the rest of us. At the same time, we all have some chance to become wealthy, not being excluded by any caste system; hence any envy or resentment tends to remain under control. Just so with supermen: they will probably be well mixed through the population, will not necessarily have any prominent stigmata, and will have little incentive to band together. At the same time, the techniques of improving people should be available to all--at a price, no doubt--and there need be no climate of envy, or hate.

This year’s meeting will also feature a presentation by Dr. Robert Hanson. Dr. Hanson is a Professor of Economics at the George Mason University in the United States and a researcher with the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University.

He is an expert on prediction markets, the social implications of future technologies, nano-technology and how these technologies influence the economy and society.

This year’s meeting will also feature a presentation by Dr. Robert Hanson. Dr. Hanson is a Professor of Economics at the George Mason University in the United States and a researcher with the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University.

He is an expert on prediction markets, the social implications of future technologies, nano-technology and how these technologies influence the economy and society.

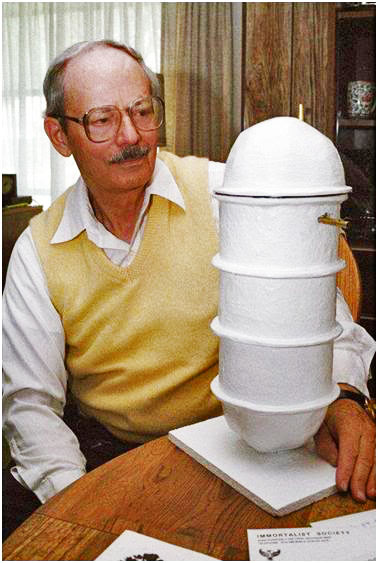

It’s hard to believe it’s been 5 years since we said goodbye to our founder Robert Ettinger. We couldn’t let this day pass without remembering his impact on us all. He remains in the thoughts of many cryonicists & friends of cryonics.

It’s hard to believe it’s been 5 years since we said goodbye to our founder Robert Ettinger. We couldn’t let this day pass without remembering his impact on us all. He remains in the thoughts of many cryonicists & friends of cryonics. Robert Ettinger waited expectantly for prominent scientists or physicians to come to the same conclusion he had, and to take a position of public advocacy. By 1960, Mr Ettinger finally made the scientific case for the idea, which had always been in the back of his mind. He was 42 years old and said he was increasingly aware of his own mortality. In what has been characterized as an historically important mid-life crisis, Mr Ettinger summarized the idea of cryonics in a few pages, with the emphasis on life insurance, and sent this to approximately 200 people whom he selected from Who’s Who in America. The response was very small, and it was clear that a much longer exposition was needed — mostly to counter cultural bias. Robert Ettinger correctly saw that people, even the intellectually, financially and socially distinguished, would have to be educated into understanding his belief that dying is usually gradual and could be a reversible process, and that freezing damage is so limited (even though fatal by present criteria) that its reversibility demands relatively little in future progress. Ettinger soon made an even more troubling discovery, principally that “a great many people have to be coaxed into admitting that life is better than death, healthy is better than sick, smart is better than stupid, and immortality might be worth the trouble!”

Robert Ettinger waited expectantly for prominent scientists or physicians to come to the same conclusion he had, and to take a position of public advocacy. By 1960, Mr Ettinger finally made the scientific case for the idea, which had always been in the back of his mind. He was 42 years old and said he was increasingly aware of his own mortality. In what has been characterized as an historically important mid-life crisis, Mr Ettinger summarized the idea of cryonics in a few pages, with the emphasis on life insurance, and sent this to approximately 200 people whom he selected from Who’s Who in America. The response was very small, and it was clear that a much longer exposition was needed — mostly to counter cultural bias. Robert Ettinger correctly saw that people, even the intellectually, financially and socially distinguished, would have to be educated into understanding his belief that dying is usually gradual and could be a reversible process, and that freezing damage is so limited (even though fatal by present criteria) that its reversibility demands relatively little in future progress. Ettinger soon made an even more troubling discovery, principally that “a great many people have to be coaxed into admitting that life is better than death, healthy is better than sick, smart is better than stupid, and immortality might be worth the trouble!”

The Lines of Research:

The Lines of Research: